What You Need to Know about Traditional Publishing Rights

Three Kinds of Rights You Should Retain When You Sign a Traditional Publishing Contract

If you like this post, you might also enjoy Two Writers on Finding a Literary Agent (free to read) and What Publishers Do for Authors.

Repeat after me: a publishing contract is not all about the advance. Subsidiary rights can offer a separate source of income at the time of publication, as well as a source of royalties and/or advances for years to come. While traditional publishers will usually include these rights in their boilerplate contract, it’s in your interest to push back and retain key rights. In this post, I’ll share which rights you shouldn’t sign over to a traditional publisher, if you can help it.

No, traditional publishing isn’t dead.

A widely-shared post by a “traditional publishing is dead!” evangelist would have you believe that the moment you sign a contract with a publisher, you surrender “creative control” of your book. The writer shares an example of a YA author whose book was made into a Netflix series without his knowledge or consent, and without financial renumeration.

Obviously, that’s a terrible story, and you don’t want that to happen to you. But this cautionary tale is the unfortunate result of an author signing a very bad contract, likely because he didn’t know what publishing rights he should control and which ones to grant to the publisher. A good contract offers serious protections and plenty of creative control to the author.

One of the most important parts of the traditional publishing contract is subsidiary rights, which often earn more for the author than the original publisher’s advance.

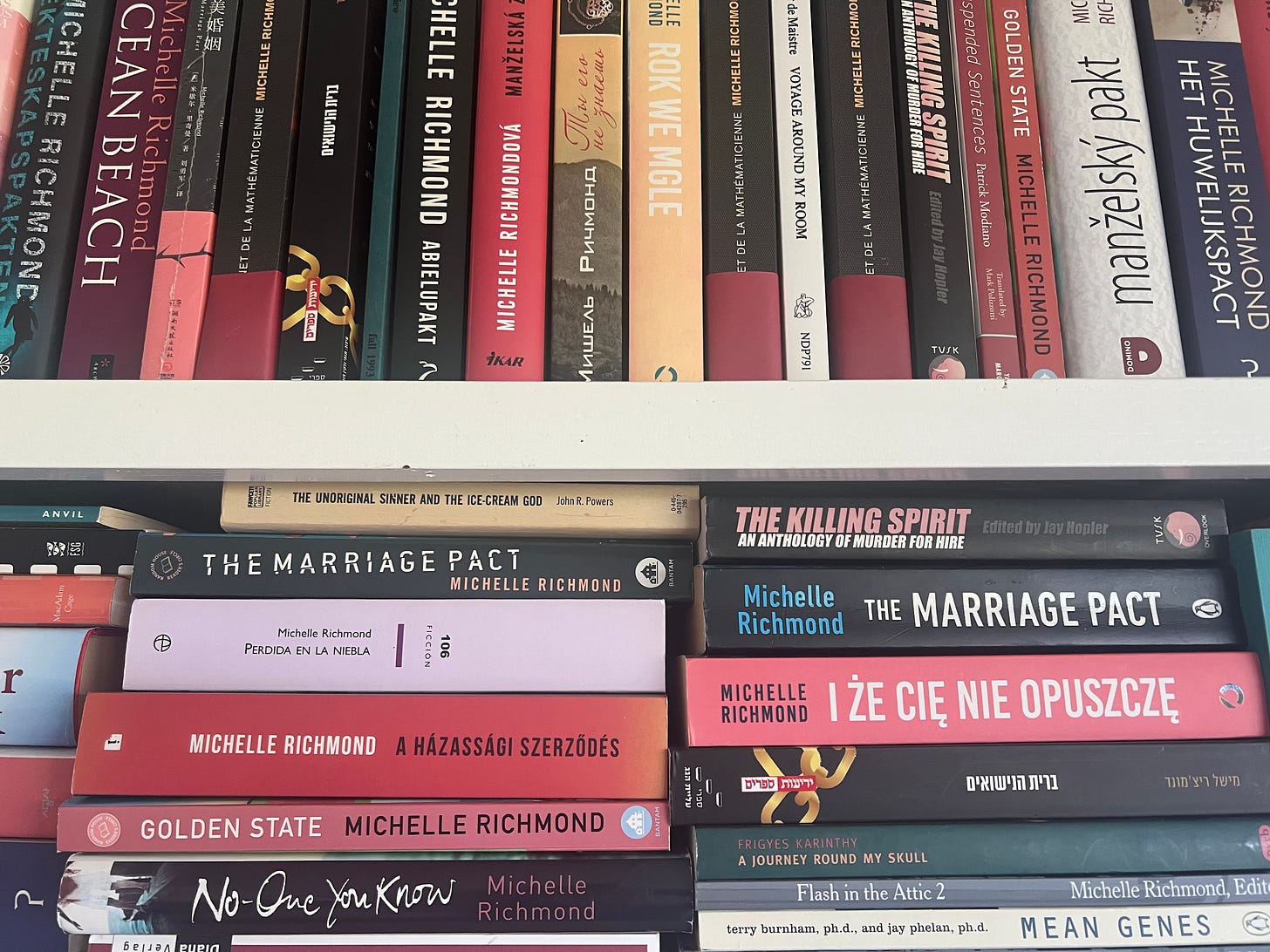

A caveat: this is my personal opinion, based on a twenty-year publishing career. I am not an attorney or agent, but I do have a very good agent who has sold rights to my books in 31 languages. Those who think traditional publishing is almost always a bad deal will tell you that only big-name authors with enormous advances sell rights in other countries, but this isn’t true. My agent has sold foreign rights not only for my bestselling books, but also for quiet literary novels that received only a small advance in the US. My novels have been optioned repeatedly for film and television and have been licensed by national book clubs, audiobook publishers, and big box retailers, including Target and Costco. My ability to make a living as a writer has hinged largely on these rights.

A second caveat: you should never sign a contract with the Big 4 without a literary agent. If you’re publishing traditionally, you almost certainly already have an agent. The agent’s job, in addition to finding a publisher for your book, is to negotiate a good contract. A good agent is the best partner you will ever have in your literary career, and my advice can in no way take the place of an agent’s advice. The agent can’t work miracles, and she can’t get a publisher that pays small advances to pay giant advances. However, there are certain things a good agent will fight for.

Where to get a contract review

I won’t go into the nitty gritty of contracts here. If a publisher offers to acquire your book, it is very much worth the small price of annual dues to join the Authors Guild and have one of their lawyers review your publishing contract—a service provided free of charge to Guild members. This is especially true if you do not have an agent—which may be the case if you’re submitting to small or university presses. Even if you’re not a member, you can access the Guild’s Model Trade Book Contract to see what a good contract looks like.

Rights = Recurring and Renewable Income

The purpose of retaining certain rights is to ensure a renewable source of income for many years, which is not tied to your publisher, your editor, or the marketing department’s enthusiasm for your book. Publishers are always in flux. Editors come and go. By retaining some crucial pieces of the rights pie to your own book, you can make sure you have something to sell for years and even decades to come. And it’s not only about making a living; each time you sell a piece of this pie, you have the opportunity to reach new readers.

Continue reading for a deep dive into three kinds of rights you should retain, and why.