Can AI Write Like Chekhov?

An experiment in literary revision

If you like this post, you might also enjoy reading What Keeps Me Up at Night When I Think About AI.

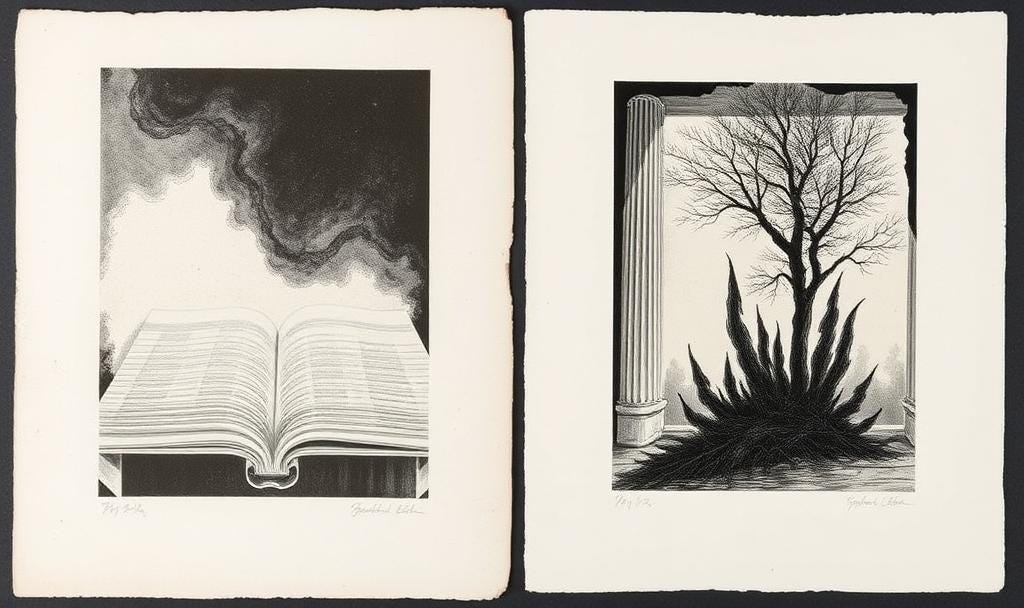

A few months ago, I decided to do a literary experiment with AI. I knew that neither ChatGPT nor Claude could write an original short story worth reading. When you ask AI to write fiction, it just feels machine-generated, much like the illustration above. This is a good thing. As a novelist, obviously, I don’t want AI to become adept at writing fiction. But could it rewrite a story? I decided to see what AI would do with a piece of original fiction if I asked it to rewrite it in a different, well-known voice.

For this experiment, I selected Anthropic’s Claude, which bills itself as being a kinder, gentler AI. Of course, I take this with a whole shaker of salt, because tech companies have been touting their good intentions for decades, even while engaging in notoriously predatory practices. Based on my own experiments, I knew Claude was at least a little better at voice than ChatGPT—less high school term paper, more nuanced. Sure, it hallucinates just like the others (any high schooler who asks AI to write a term paper will end up with a bunch of phony quotes from nonexistent sources). But I wasn’t asking it to do research. I was asking it to read my story and make it the same, only different.

Since tech is known for large-scale theft of intellectual property, I didn’t want to feed it an unpublished story. I wanted to go with something low-stakes, so I chose a flash fiction I’d written in 2022 about familial complications, featuring an intrusive squirrel—A Practical Removal.

If you’re so inclined, you can read the original flash fiction here.

Although AI was trained on a vast trove of original work without the authors’ or rights-holders’ consent, including copyrighted works by writers who are still very much living today, for my exercise, I chose to ask Claude to rewrite the story in the style of a writer whose work has entered the public domain. Thus armed with my low-takes source material, I fed Claude this prompt:

Rewrite this story in the style of Chekhov.

And then I went down the rabbit hole—or into the squirrel’s den.